Marrickville: Is there no alternative?

Chapter 4

Dirty Shirlows, Vibe Tribe and the speculative fiction of the rave utopia

Dirty Shirlows in Marrickville was a haven for the marginalised of the marginalised. Punks, anarcho-syndicalists, drag queens, artists, you name it; they all adopted the place. Between 2008 and 2012, under the watchful eyes of a female duo, who were concurrently booking agents, carers, guard dogs and matriarchs to Sydney’s underground, Dirty Shirlows became a revered, unlicenced venue.

Walk the floors of Dirty Shirlows and you will receive an alternative history of Marrickville. This history sticks to your feet, impossible to shake off. Blood, sweat and beers. Layer upon layer like sedimentary rock. There’s something almost geological about this archive. Starting at your feet, the sensation of the muck rises up through your body like a volcanic eruption, spewing forth the building’s deep-buried secrets into your head.

Concrete whispers. Slip and you might fall into a parallel world.

“The floor of Dirty Shirlows is untreated concrete”, Matty K says, a former resident and sound engineer at the unlicenced DIY venue. “It soaks everything up… You can’t really walk on it in bare feet because your feet get instantly crusty from all that history.”

Prior to the creatives and sound terrorists moving into Dirty Shirlows, the previous owners used the space for illegal dog fights. Matty remembers there still being blood stains in the concrete at Dirty Shirlows during the first gigs there in 2008. In the corner of the warehouse there were stacked cages like an exhibit in a masochistic torture museum, transforming the rave experience from escapism to voyeurism. Rotating displays of street art smothered the walls. Adding to the atmosphere was the penchant of the early Shirlows residents for breakcore and experimental noise.

“It was just a really heavy vibe”, Matty explains succinctly.

Subversive performance was a safeguard – an extension of the self-regulating nature of alternative clubbing cultures. It ensured that like-minded audiences populated the space. Punters knew not to blab about the venue, not to loiter on the streets outside during a gig and not to harass other attendees. Prepare to get freaky, performers warned, in roundabout ways.

Recounting his favourite memories of Shirlows gigs, Matty pinpoints the “shock value” of the folk-punk band Rica Tetus whose performances were straight out of the Eric Andre handbook. “The lead singer, could vomit on cue. He would do this thing halfway through his set where he would vomit into an old helmet and then put it on his head and continue to play the fiddle. It was off the chain gross. But if Rica Tetus was playing, you knew it was going to be a wild time.”

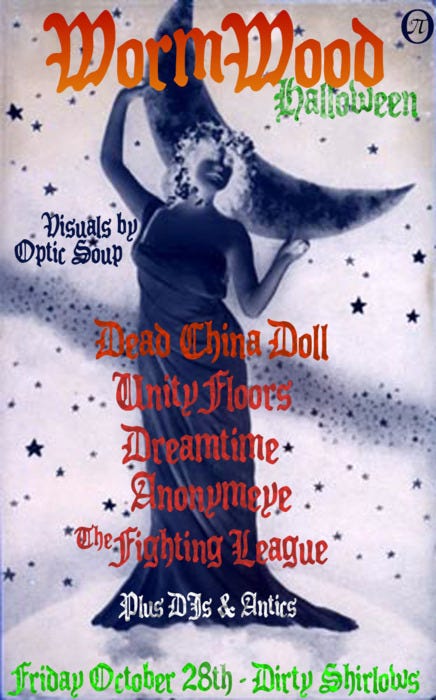

Poster for the Wormwood Halloween gig at Dirty Shirlows - another event Matty highlights as particularly memorable. The Octopus Pi crew worked on this production.

It’s difficult to isolate particular sounds that defined Dirty Shirlows. The music on display was diverse.

If there were shared sounds, they usually involved punks thrashing on electric guitars and drum kits and DJs discombobulating crowds with the formula alchemy and tempo fuckery of breakcore. Pulsating bass and fast breaks. A sprinkling of hard techno and speedcore here and there. A stretch of the vocal chords now. Deep guttural shouting. Lo-fi distortion was a matter of pride not an indication of amateurishness. These musos were Iron Chefs, slicing and dicing. They served up gigantic hot pots loaded with chilli for these family dinners/Shirlows nights. The sets were not necessarily easily digestible. They contained a kick. Pushing the boundaries of recognised genres, they tested the digestive system of punters and inflamed stomach linings. But they also cleansed airways. Coming to Shirlows, you knew you were getting a hearty meal.

DJs chopped up dance tracks and meme samples at a frenetic pace, capturing a niche somewhere between improvisational free jazz and drunken button jamming. Hardcore punk singers kicked over chairs and launched themselves into the air, surrendering lyrics to laboured gasps for air. There was always anti-establishment energy.

Punk and rave, after all, have a lot in common. Hardcore punk was a volatile critique of the stardom of 70s rock’n’roll. Dissonant melodies, shouted vocals, disruption, excess, disdain for public and private property and outsider status in a capitalist system defined punk. In the face of commodification, political activism and direct action became essential for authenticity.

In contrast to arena-filling rock’n’roll gigs with fireworks displays, punk fans came face to face with their heroes in crowded taverns and squats. “A band was on the same level as the audience, sometimes literally, and at most performing on a small stage a foot or two above the floor”, writes music historian Simon Reynolds on the mid-70s pub rock rebellion in London against “hippiedom and progressive music”. In Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past, Reynolds highlights the “intimacy” of these gigs which spawned the punk movement. Standing at the front of a mosh pit, you could “smell the beer on the singer’s breath”. Head-banging guitarists and frantic drummers, arms like scythes, splattered those in the front rows with sweat. Singers might jump into a circle pit to mosh.

Dance music culture – during its humble beginnings at least – celebrated collectivism, democratised music and event production and, like punk, disintegrated the passive spectator/genius performer dichotomy embedded in rock.

Both punk and rave have found refuge in the shadows; in unlicensed spaces, overlooked venues and occupied territory. Many describe underground music spaces like Dirty Shirlows as “temporary autonomous zones” (TAZs).

In his 1991 text T.A.Z: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, Hakim Bey coined the term TAZ to describe everyday occurrences and non-hierarchical spaces within late stage capitalism which break apart social norms and resist control from state authorities. By proving what is possible, a TAZ would allow participants to creatively rethink social relations.

Punk’s affiliation with illegal partying, however, appears to be on the wane as band nights go out of fashion. Indeed, what made Dirty Shirlows distinctive as a warehouse venue was the frequency of band nights.

The residents invested significant time, energy and funds in the audio set up. Matty and housemate Corey, who was studying sound engineering at the time, ran a tight ship. Matty describes the initial speaker set up as a “total mess”. He convinced his housemates to invest in an audio desk, which enabled them to expand into ever-more sophisticated events. Live bands quickly became a staple. “It’s so much easier to just set up some speakers and a DJ desk”, Matty says. “To do live bands, you need heaps more audio gear, but then you also need people who are knowledgeable enough to be able to run that… You can’t just set up a couple of mics on stage and cross your fingers and hope for the best.”

At some points, Matty says, they were doing three gigs a week – cabaret nights, psych rock gigs, drum’n’bass raves and everything in between.

Despite the increasing professionalisation of the sound setup, Shirlows always remained first and foremost a community space. Fundraising was common and tickets were cheap. Often 5 or 10 bucks or a gold coin donation.

A Wormwood UV party at Dirty Shirlows in December, 2011.

* * *

In an era of rising techno-totalitarian state surveillance, us Sydneysiders often feel like lab rats, scurrying around cages under the watchful gaze of invisible forces. DIY events, however, are an affront to capitalism – a refusal to drink from the tubes lowered into our enclosures with drug-laced liquids. They are also a collective prison break. They have enabled Sydney’s young population to escape observation. I’m talking about the kind within urban ruins — warehouses, abandoned stadiums, empty office blocks and squats. By virtue of location, organisers and attendees partake in law-breaking. Maybe you’re cutting barbed wire and padlocks to wheel in gear. Maybe you’ve reclaimed public space or occupied private property. You’re hyper-aware of the space’s material conditions and who you’re up against. This is partying as civil disobedience.

* * *

8 PM, March 12 2022. Vic on the Park, Marrickville.

Rub too close to the bodies next you and you might just receive an electric shock. People stamp and howl like horses chewing on the bit at the starting gate. “Push up. Push up. Move up. Hey, hey, hey. Keep it coming, keep it coming. Before we start we just want to pay respects to the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. This show is taking place on stolen land. Sovereignty was never ceded… This is a hardcore show now MOTHERFUCKER”, Jem Siow roars into the mic amid opening guitar chords and a tease of the drum kit.

“Respect this, boy. Respect each other and mosh hard as fuck. This is a gang called SPEED, babyyyyyy”. The band launch into their hit track We See U and the crowd is entirely up for it.

The room is a maelstrom of elevated heart rates, pent-up frustration, masochistic delight and energetic release. The closer you are to the centre of the thrashing bodies, the more reality bends at the edges. A couple of women howl, screech and shove, holding their own. Some attendees jump onto the stage where they windmill and two step within touching distance of the band members before belly-flopping into the crowd. A few brave souls flip and cartwheel into the heaving mass of non-descript body parts, feet in the air, as if a practical joker has shoved a nest of upside-down turtles down a slide at Wet’n’Wild. There’s no boundary between band and spectator.

A confused seccy attempts to create order at the front of the dancefloor, succeeding only in earning himself a flurry of elbows to the head.

It’s in this room, on board this Shinkansen of chugging basslines and discombobulating metalcore rhythms, that I realise this is exactly how Sydney music should sound.

As a resident in Sydney’s Inner West, a supposed countercultural heartland, I’ve become accustomed to vastly different modes of creative operation: whisper-territory white-walled art galleries where audiences sit cross-legged and illegal raves in unlicensed spaces where passive spectators share cuddle-puddle nangs and vibe out to ambient soundscapes and bush techno. These art scenes tend to prioritise irony, hedonism, silliness and performative narcissism – impotent responses to late stage capitalism that subdue our political impulses.

Yet Sydney consistently ranks as one of the most expensive cities in the world. Like paint thinner, rent costs here strip the walls of rickety bank accounts and lather the decaying foundations of our financial security in flammable liquid, attracting cashed-up junkie wheeler-dealers addicted to the vapours and negative gearing. According to Demographia’s International Housing Affordability 2023 Edition, Sydney is the second least affordable city in the world for home purchasing. Domain’s December 2022 Rental Report, meanwhile, reveals that Sydney is currently experiencing its steepest annual rent growth since 2008, and Marrickville is at the forefront.

Those Domain figures reveal the median rental asking price for Marrickville homes rose 4% in the 12 months to December 2022 (to $780 per week). In the same period, the median rental asking price for Marrickville units sky-rocketed 13.6% (to $500). Figures from the property industry research firm CoreLogic reveal that, across the last 30 years, the “best performing” sub-region in Sydney for dwelling values is Marrickville-Sydenham–Petersham where they have increased 660%. Put another way: no other area in Sydney has gentrified as rapidly as Marrickville in recent memory. It doesn’t exactly bode well for the sustainability of creative practice.

So why aren’t the city’s creatives angrier?

Listening to SPEED that night at the Vic though, I’m overcome with relief.

This isn’t a band with an archive of albums. It’s a bunch of mates taking a stand against the system – a 25 minute burst of teeth-clenching, spit-producing rage that makes me proud to be from Sydney.

I’ve never seen the Vic so packed.

From exhibitions and shows at 108 Warehouse in Marrickville, the Factory Theatre, the Great Club and Bottega Made near Sydenham Station to their infamous Vic on the Park set – all their gigs are infamous, mind you – Marrickville seems to be home turf for the hardcore band SPEED. It’s an appropriate gig location. Marrickville is a middle ground between Sydney’s north, south, east and west and a melting pot. It’s a reflection of everything the band represents.

But it’s telling that they’ve become a symbol of diversity in Western Sydney. The band have adopted the Inner West but the members originally hail from everywhere in Sydney but the Inner West. They’re from the city’s geographic fringes. Take note.

SPEED have amassed such a large following so quickly because they’ve managed to do what almost no one else has: they’ve united Australia’s underground. Their openness to new fans has galvanised their meteoric rise in a territorial scene where newcomers are shunned and mocked far too often, where bruises, scars and broken bones are badges of honour and tattoos and patches, sewed onto jackets, are considered visual representations of authenticity. Go to a SPEED show and you’ll find ravers and hip hop heads galore. A SPEED show is a convention for musical anti-establishment degeneracy with a list of names on the run-sheet drawn from the holy triumvirarte of hardcore punk, hip hop and hard techno: AWOL, Concrete Lawn, Mulalo, Nerve, Posseshot, Fukhead, PTwiggs. It’s only a hop, skip and a jump away from the sense of community, DIY spirit and inclusivity that sustains Sydney’s underground rave culture.

It’s unfair to claim hardcore ever died in Australia, but SPEED have near single-handedly hauled hardcore out of the doldrums of irrelevance and into the limelight. That they did so from the Emerald City – home turf for corporate yes-men – is fitting. I doubt Melbourne could have produced this level of determination. To stick around in Sydney as a creative, you have to be a little cracked in the head or a diehard motherfucker. That’s probably why SPEED have attracted international fandom while other local bands – equally deserving – are yet to break through. They’re grafters.

A common refrain that the band members repeat at live shows is their lack of difference from audience members and their lack of experience. We are you, they say. Anyone can do what we’re doing.

There’s no them in the SPEED cosmos, only us.

Wherever they go, SPEED make a statement. It’s not just because of their racial composition – predominantly Asian – in a scene that’s historically white or because of their knack for calling out racism. It comes down to the intensity of their music, which they refuse to dilute amid international acclaim and the circling of industry professionals, and their groundedness. It’s an intriguing sight when they simultaneously catalyse circle pits and preach unity. Despite the macho bravado of hardcore punk, their stage presence is remarkably humble.

“I see a lot of new faces in the room”, Jem Siow shouts at the Vic on the Park. “If it’s your first hardcore show, put your hand up. Yo thank you for being here. I really appreciate that. This is a hardcore show. If you get hit it, it ain’t personal, ok”, Jem instructs at the Vic. ‘This is how we do things. Thank you for coming into our world. Please respect what we do. It’s all out of respect and love. That’s the bottom line here. Always remember that shit.”

* * *

Punk and rave have a shared history in Sydney – one that precedes Dirty Shirlows.

Recognising a particular contiguity between the harder ends of the punk and techno spectrums in his essay ‘Making a Noise – Making a Difference: Techno-Punk and Terra-ism’, anthropologist Graham St John has traced the continuation of anarcho-punk politics in Sydney with the city’s techno explosion. As the 80s waned and the 90s took over, there was a sharing of equipment and personnel between the anarcho-punk scene and early techno collectives such as Vibe Tribe. At the communally-owned Jellyheads venue near Central Station, punk bands, DJs and live electronic acts shared the stage until electronic music stole the limelight altogether and Vibe Tribe was born.

Sound system crews including Vibe Tribe and System Corrupt drew direct inspiration from anarchist theory, publishing manifestos and producing zines which espoused the revolutionary potential of the TAZ. They reclaimed public space. The brickworks amphitheatre in Sydney Park, Alexandria, became one such stomping ground. There you might find Non Bossy Posse (NBP) playing. The group sampled advertisements and radio segments. Tossing commentary on Indigenous land rights, social justice and environmental sustainability into a headwind of pre-programmed techno and trance beats, NBP pinpointed the dancefloor as the target of their sonic, political cyclone. According to Kol Dimond, a member of the anarcho-pop punk band the Fred Nihilists and later NBP, this was live “finger looped mayhem”. Their music was “very techno and very acid… generally anywhere between 140 and 160 BPM [beats per minute].” NBP represented the “same politics, same passion for systemic social change, just a different soundtrack.”

Dan Conway, meanwhile, a devout Vibe Tribe member, proudly describes himself to me as a “foot soldier in the techno revolution”. He pushes word through the phone with a staccato rhythm, rotating between crescendoing rapid-fire sentences and re-centring caesuras. Later he sends me long paragraphs over Facebook Messenger.

“There were people who would turn up with fancy hairstyles and they were superstar DJs and they had a lot of cultural cachet”. But many within Vibe Tribe were against hierarchy and the idolisation of performers. Vibe Tribe dancefloors were often circular with speaker stacks in four corners. “People danced with each other. It was a collective experience”, Dan says. “Nearly always the DJs were put on the same level as the dancefloor or hidden away in a corner — maybe behind a curtain”. Dan and Kol would allocate themselves the unglamorous jobs of digging shit pits and fetching water in the middle of the night. This was a “utilitarian workers approach”.

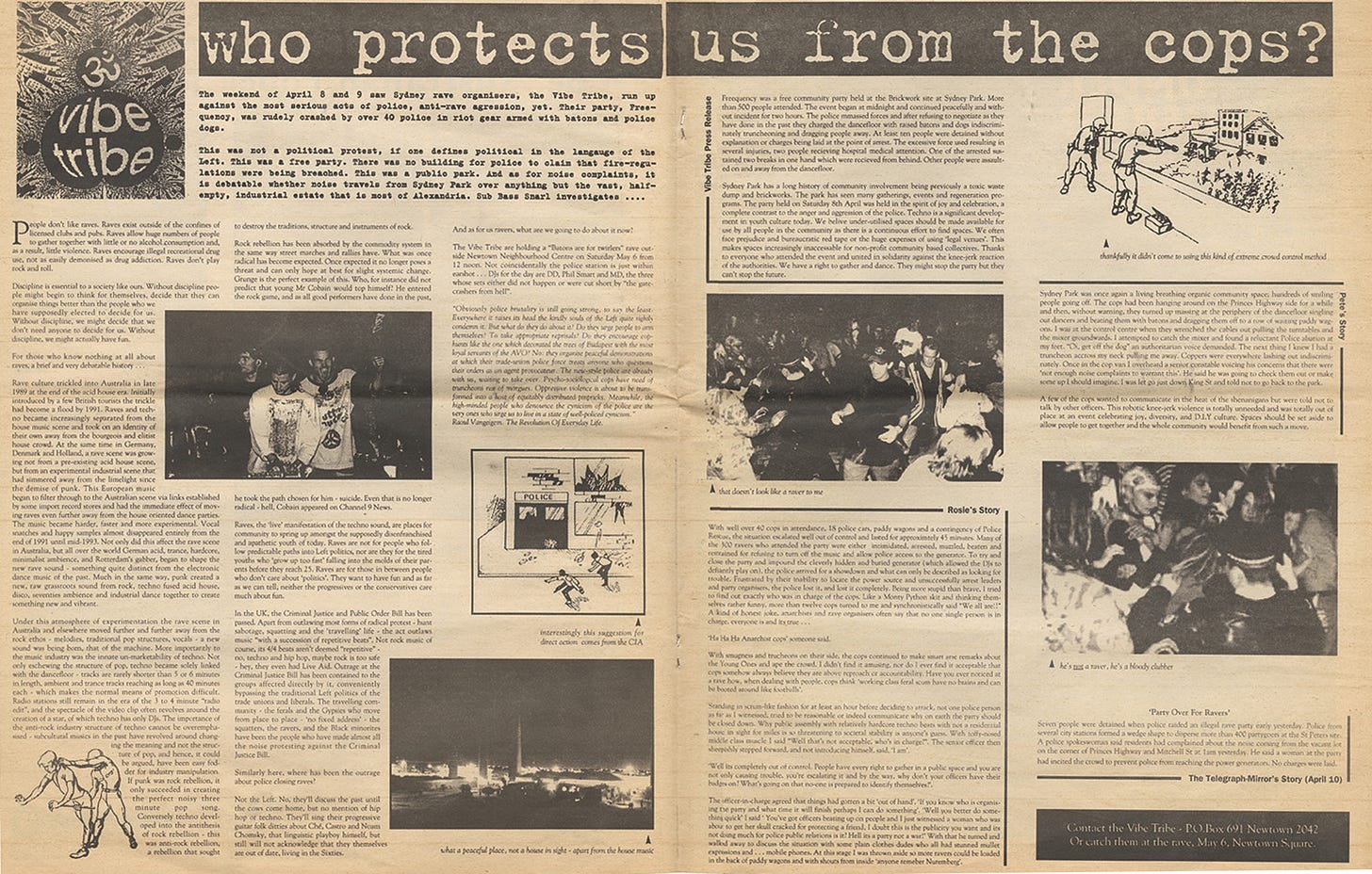

The free Vibe Tribe party Freequency in Sydney Park in April 1995 appears a salient moment in cultural memory — one which shocked, angered and radicalised those present. 40 to 80 cops turned up that night.

Dan Conway was police liaison. “It immediately became clear that they were not interested in negotiating… They knew what was going on and they had orders.” The riot squad and dog squad amassed forces on the edge of the dancefloor. “We very quickly understood what was happening and what was going to happen, and everybody stayed”, Dan recounts. A techno track with bagpipes pulsated through the park — DJ Dee Dee steadying the troops. Dogs growled. Then, moments later, the police moved in, indiscriminately beating members of the crowd, which was anywhere between 500 and 2000 strong, depending on who you ask. Swirling black truncheons created shadows over the grass as if a giant vulture was spreading its wings.

With organisers rallying the crowd over the mic, people formed a circle around the speakers and decks, preventing the police, initially anyway, from cutting off the music. This was not misbehaviour by intoxicated revellers. Kol asserts that it was a coordinated effort in an already highly politicised space — just one of many plans inscribed in the Vibe Tribe manifesto to “deal with skinheads or thugs or coppers.” According to one account, police “couldn’t deal with the concept of ‘everyone being in charge’”.

At 2am, having regrouped, police charged the dancefloor in a wedge formation with batons, shields and dogs and carried off the generator. Some punters were hospitalised, countless injured.

Rumours swirl around the Freequency event, shrouding the event in a haze which makes fact hard to separate from fiction. But the Freequency story is a familiar Sydney story — one tied to the violence of law enforcement, inner city gentrification and the policing of pleasure. An Ombudsman report later found that the police had over-reacted and used excessive violence, but there were no repercussions for the police involved and little media attention was given to the ferals in the park, besides some sympathetic articles in the UNSW newspaper Tharunka, although newspaper articles deriding raves more generally as drug-fuelled playgrounds were aplenty.

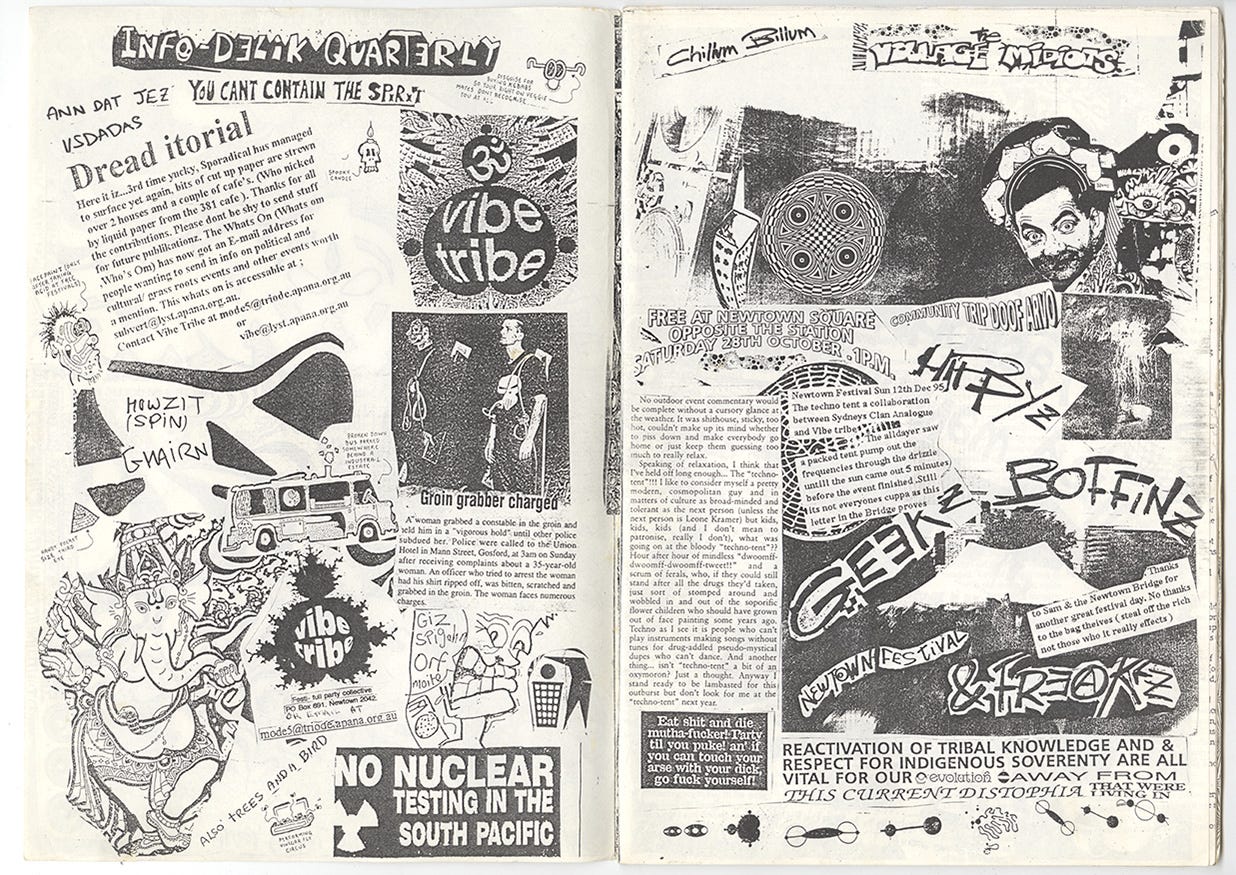

UNSW newspaper Tharunka covered the police brutality at Freequency (above). The Vibe Tribe zine Sporadical (below). Images courtesy: Dan Conway.

Soon after Freequency Vibe Tribe led a 500-strong protest against police brutality in Newtown. A fundraising event opposing the construction of a motorway through Sydney’s rapidly disappearing bushland, Carmageddon, followed on from that.

In the late 90s, Vibe Tribe took their sound system into the desert, linking up with Indigenous land rights campaigns and anti-uranium mining protests. As Vibe Tribe morphed into other collectives — Ohms Not Bombs and Lab Rats, for example — these new groups shouldered the responsibility of linking the inner-city anarcho-rave scene with First Nations communities, earning themselves the label “techno terra-rists” from Graham St John. As if the worlds of Mad Max and Lawrence of Arabia were blending with the universe in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, these activists ventured into regional Australia using a series of buses and trucks adorned with graffiti and laden heavy with speakers and generators. One of these iconic vehicles was the Lab Rats van which hauled a trailer with a solar-powered PA and a wind-powered cinema across Australians sands. The engine was converted to run on vegetable oil.

In Dan’s eyes, he was truly living anarchism at this time. He is quick to delineate between raves (back then a “dirty word” describing expensively-ticketed stadium events) and free party culture. He is also quick to suggest that this was a unique historical moment, and he is right. Few events these days match the scale and shared understanding of politics which defined Dan’s cosmos.

The next generation of Australian ravers and doofers never quite maintained this momentum. By the late 00s, cultural critics such as Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher had adopted the term “hauntology” to describe a thematic ghost which was haunting contemporary culture. This was the spectre of the lost futures we had previously imagined in our literary fiction, films, music and politics. In his essay ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology’, Fisher expanded upon this concept, arguing that contemporary music had “lost its sense of futurism” and largely succumbed to “the pastiche and retro-time of postmodernity”. The optimism of 80s hip hop and the 90s rave revolution was waning.Within electronic music – the supposed herald of the future – technological advancements were enabling artists to sample old pop hits and layer soundscapes of dated radio jingles and advertisements over their tracks more easily, and more cheaply, than ever before.

Simon Reynolds applied this theoretical framework to a broader swathe of culture. In his 2011 book Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past, Reynolds argued that we were in the midst of a “pop age gone loco for retro and crazy for commemorations… Instead of being about itself, the 2000s has been about very other previous decade happening again all at once: a simultaneity of pop time that abolishes history while nibbling away at the present’s own sense of itself as an era with a distinctive identity and feel.” Musicians were pining nostalgically for past sounds, recreating and rehashing them obsessively like museum curators. “The 2000s were dominated by the ‘re-‘ prefix: revivals, reissues, remakes, re-enactments”, Reynolds writes in Retromania. “Endless retrospection: every year brought a fresh spate of anniversaries, with their attendant glut of biographies, memoirs, rockumentaries, biopics and commemorative issues of magazines. Then there were the band reformations…”

With self-awareness, some artists, Fisher argues, intentionally turned to “the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past”. Fisher located this latter type of sonic hauntology within drum and bass, dubstep and experimental dance music. For these artists, filling their tracks with the voices of the dead, spectral harmonies and vinyl crackle was a kind of metaphysical comment. The emphasis in this sombre music on time being out of whack illuminated the particular hauntological precondition of late stage capitalism. Such music was a response to, not a symptom of, capitalist realism. But this style of music was rare.

Put another way: the 00s offered distinctly less forward-thinking creative production. This cultural inertia was not just a deterioration of creative thinking, Fisher and Reynolds suggested; it reflected a deeper collective mourning of the past failures of state communism and an acceptance of the status quo.

Given: within Sydney there have been brief flashes of imagination and cultural shifts in recent years, some of which I have documented elsewhere. But as the optimism of the rave utopia dissipated in the 00s, only the more experimental electronic music communities continued to plug away with free party culture. Many turned their backs on rave culture. Numbers dwindled.

With unlicensed venues such as Dirty Shirlows, Marrickville was a lone stronghold in Sydney, holding out amid a cultural famine. But the imaginative impasse of capitalist realism has proven to be a formidable enemy. Choked half-hearted whimpers have replaced the anarcho-punk battle cries of yesteryear.

Marrickville today is a long way from five buck Shirlows gigs.

* * *

In the late 00s, before he moved into Dirty Shirlows, Matty was living in a warehouse on Faversham Street with the Figureight collective. The food there was communal. Much of it was obtained via dumpster diving. “The money we were pulling in from parties went towards our rent. So people who worked on parties got what we would call rent credits.” Matty had quit his full-time job. Instead, he was doing odd jobs as a freelancer in television audio. “It was a period of my life where I was almost existing without money”, he says.

According to Matty, Figureight was a “political act”. Embedded in the activism scene, the crew provided audio for numerous protests. Behind-the-scenes they supported Reclaim the Streets and Reclaim the Lanes.

Before the handle-bar moustaches saturated Marrickville, there was more unshaven stubble. Matty recounts that a friend, with whom he started the Figureight collective, moved into another Marrickville warehouse in the late 00s to start a legitimate business. “When he moved in, it was full of bullet holes. It had this huge anti-bullet structure – this wall at the front of the warehouse that they had to knock out and a thick steel door”. The Chalder Street site, shot up numerous times, had been a fortified club house for the Nomad motorcycle gang.

“If you wanted to go out on a Friday or a Saturday night and you didn’t have any knowledge of the warehouse scene, you wouldn’t go to Marrickville. There was nothing there”, Matty explains. “The [Marrickville] bowling club now puts on heaps of gigs. They weren’t putting on gigs back then. It was just this seedy old bowling club.” Today the area is different – “full of breweries” and people who “don’t look particularly alternative”. Few jagged edges remain.

Marrickville today lacks free party culture, 24 hour house parties and cheaply-ticketed warehouse events. What underground subcultures remain are distinctly apolitical. Illegal party organisers are quick to comply to police directives when they turn up and crowds — often there only for a short time and a good time — are quick to disperse. I have never seen a crowd respond like they did at Freequency.

Festooned with gaudy white picket fences, Marrickville feels like a giant infirmary. It’s all stainless steel, pastel furniture, minimalism and white walls now. Glossy, sanitised surfaces have supplanted brick and lino. The suburb bares its teeth with plentiful graffiti but peel away the paint and look inside those buildings and you’ll find something more akin to a photography spread in Kinfolk. It’s more cottagecore than eshcore.

Where the iconic warehouse 2Flies used to be, there is now an art gallery. Saywell Gallery. The new owners have painted the walls white and installed smooth, polished floorboards with military discipline. Everything is equidistant, in line, to the millimetre. In one of the gallery’s Instagram posts, a framed mock cover of Vogue hangs on the wall. The image is black and white, as if ripped from a previous era.

Marrickville is a place of permanent renovations. As fresh layers of paint splatter bricks walls, the ephemeral nature of the suburb’s graffiti combines with the speed of gentrification and the recent influx of chic small businesses to give locals a sense of frenzied newness. Marrickville’s manic pixie girls, e boys and goth enbies – some of the suburb’s dominant personality types – curate their lives and market themselves online in a relentless game of schizophrenic post-modernist style-surfing where outward representations and fashion, ever subservient, adjust breathlessly to the pace of consumerism. It’s a game of online renovations. They trade and swap identities like they’re Yu-Gi-Oh cards. Cottagecore, Medievalcore, swampcore, Y2Kcore. There’s an endless list of -cores popping off in cyberspace right now.

Is their fashion, like Marrickville’s culture more broadly, a new hybrid style, never seen before, paving the way into the future? Or is it simply a regurgitation of past fads – proof of an inescapable time loop? Does this dynamic (entrepreneurial?) environment – what Ben Agger terms “fast capitalism” – mask the cultural inertia behind closed doors?

A 10 minute dig through Domain’s archives online show that Marrickville’s bohemian streak is a major selling point to wealthy home-owners, few of whom, I imagine, frequent the ceramics workshops or ten-hour DIY raves in the surrounds.

I’m drawn these days to Murray Bookchin’s polemical essay Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm. Bookchin argues that Bey’s concept of a “TAZ” and temporary ferality exemplifies the “lifestyle anarchism”, “social indifference”, “egotism” and disinterest in revolution of young, urban professionals: “a TAZ is a passing event, a momentary orgasm, a fleeting expression of the ‘will to power’ that is, in fact, conspicuously powerless in its capacity to leave any imprint on the individual’s personality, subjectivity, and even self-formation, still less on shaping events and reality.”

I’m not quite as pessimistic as Bookchin. I believe that certain DIY events, when organised carefully, foster a functional politics. But they are few and far between.

On the one hand, raves and doofs have always been refuges for disenfranchised communities and self-proclaimed freaks with alternative lifestyles. Dancing offers opportunities for fundraising, for the self-expression central to combatting queerphobia, even for political radicalisation and alliance-building.

In the inner west, however, where profit-minded forces have commercialised raves, they have also become sites of exorbitant drug-taking and debauchery. Middle-upper class kids and office slaves disappear into the capitalist apocalypse, number by the drugs in their bodies and dumbfounded by the sensory assault. There’s the potential that the spiritual relief of the rave merely makes them acquiescent. Upon returning to reality, refreshed, perhaps they’re better able to endure the status quo and ascend corporate ladders.

For years Marrickville’s DIY party scene has dug trenches on the precipice of commercialisation. Disillusioned leaseholders hiked prices as police interference crushed alternatives. Market monopolisation eventuated. 3, 4 grand for a six hour event on the weekend… Somebody’s having a laugh. Friends of mine have lost thousands of dollars on Marrickville warehouse parties. Punters too have shouldered costs. But we can’t lay blame at the feet of the humble renter. Sydney’s housing market lurks in the background. It’s an age-old story in the harbour city: shallow landlordism and housing-as-profit, destined to force the city’s cultural resistance to run aground.

Post-lockdown, ticket prices are the same if not even more expensive. Warehouse party tickets now cost between $20 and $60, sometimes even more. Questions must be asked about the durability of anarcho-punk politics. Increased prices of entry in Marrickville and its surrounding suburbs and improving public acceptance of dance music have seen digestible, non-confronting music — tech-house and disco, for example — enter the warehouse.

Hardly the soundtrack of protest.

* * *

The go-to critique of the TAZ is that it is indeed temporary; it’s incapable of wide-reaching influence.

That’s not to say anyone intended or expected a small DIY venue like Shirlows to change the world. Most of the time partying is about enjoyment and connection. It doesn’t need to be more than that. But Shirlows did become a hub for community, a hidden gem, rebooting Sydney amid system shut-down alongside warehouses like Maggotville and Sashimi.

Sadly Dirty Shirlows was no exception to the ephemerality part of the TAZ equation. Increased scrutiny catalysed its demise. In 2011, the community radio station FBi nominated Dirty Shirlows for a revered SMAC award – best collective. Dirty Shirlows came out an unexpected winner. Days later, council representatives and police came knocking, demanding to know the score. “The place didn’t have a DA [development application] to do what we were doing”, Matty explains. Fire safety – no sprinklers or fire escape – was another issue. “That was it for us. There were already some tensions and interpersonal issues in the warehouse.”

One Sydney promoter, who ran events at Dirty Shirlows, tells me a slightly different story. Requesting anonymity, he explains that over time the founding politics dissipated. “The amount of shit cunts attending grew, heat from the council grew and then they started abusing promoters”, he claims. “They thought they could get away with anything.” Divergent narratives of Shirlows grow almost naturally out of the complexities and difficulties of sustaining a venue without licencing – it’s hardly a stable environment – and making definitive statements and finding sure footing amid drug-fuelled revelry is a difficult task. This contributor’s opinion isn’t necessarily a popular one.

In the aftermath, the Shirlows crew teamed up with the very authorities who had closed down the warehouse. Benign intentions no doubt. They worked with Marrickville Council and a Live Music Taskforce to prolong the life of other similar Marrickville spaces, to prevent a repeat, but doing so involved discussions of licencing.

In short: it involved an exit from the underground.